Adolescents face unique challenges accessing reliable health information and education. This has become even more difficult in a post-Roe landscape where publicly available health information on government webpages continue to be suppressed, federal and state level reproductive policy changes and legal challenges persist, and mis- and dis- information about health—particularly, reproductive health issues like abortion and contraception—are widespread. Over the last several years, teen pregnancy and birth rates have fallen; however, rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) remain high among teens and young adults. Many schools and community groups have adopted a broad spectrum of programming that ranges from curricula aimed at reducing teen pregnancy and STI rates—which can include topics like contraception as well as broader aspects of adolescents’ reproductive health such as forming healthy relationships—to curricula that emphasize abstinence and avoidance of all sexual risks. The content of these programs varies considerably and is shaped by policies at the school, district, state, and federal level.

Over the years, Congressional, legislative, and executive agency actions have both hindered and expanded access to federal funding for comprehensive sex education depending on the administration and partisanship. Most recently, the Trump administration’s executive order officially recognizing only two sexes—male and female—has far-reaching implications for the LGBTQ+ community and education. The proclamation has affected how federal agencies run health programs, collect data, share health information, and will also shape whether state and local sex education programs supported by federal grants like the Teen Pregnancy Prevention program, will continue to qualify for support.

This issue brief reviews the major sex education models and funding streams that are most commonly used, highlights state policies on sex education, and summarizes what is known about the impact of these programs and policies on teen sexual behavior and health outcomes.

Sources of Sex Education

Adolescents receive sex education information from a wide array of sources including informal channels such as parents, friends, online or social media, or through formal settings such as school or health care professionals. For example, while most teens learn about condoms—the most commonly used contraceptive among teens—in formal educational settings and through their parents—a 2024 study on youth health access found, not surprisingly, that many teens also get their contraceptive information from friends and online through websites and social media.

Most youth use social media and nearly half are online almost constantly on platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram. While social media can be an effective tool to spread reliable and trustworthy health-related information to young people, it can and has been used to spread mis- and dis-information. Anecdotally, a growing number of young women have reportedly stopped using hormonal oral contraceptive pills after viewing TikTok content describing negative experiences with the pill.

Parents can be another source of information for adolescents. Most female adolescents say they discussed “how to say no to sex,” birth control methods, and STIs/STDs with their parents. Most male adolescents discussed STIs/STDs with their parents (55%), but fewer than half say they discussed any other sex education topics. While most adolescents aged 15 to 19 say they received some sex education from their parents, one in five adolescents say they did not (Figure 1).

Parental involvement also plays a role how or whether students receive sex education from schools. Most states (45 states and D.C.) have “opt-in” and/or “opt-out” policies for sex education, meaning that parents can choose to remove their student from classes that include sexual content or must approve their participation in classroom education on the topic. Nonetheless, many teens say they received sex education in formal settings such as schools and churches. Most reported getting information about STIs/STDs and HIV/AIDS prevention and “how to say no” to sex in a formal setting (Figure 1). Far fewer adolescents, however, say they learned about birth control methods or waiting until marriage in classroom settings. Fewer than half of adolescents say they received education on where to get birth control.

State Policies and Sex Education Models:

Impact on Youth Reproductive Health

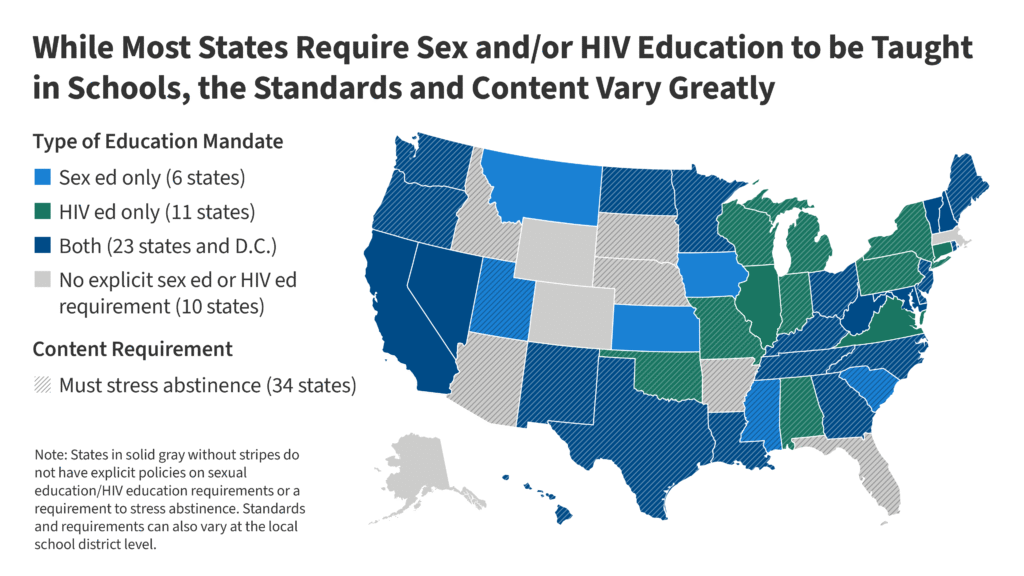

Most states and D.C. require some aspect of sex education be taught in public schools (Figure 2). However, the decision-making process over implementation of sex education varies on both the state and local level, resulting in different interpretations of program models and content, as well as the timing and overall quality of the sex education provided to children and adolescents.

In most states (43), local school districts and sometimes individual schools develop their own curricula, but state-level officials play a role in curriculum development in seven states (North Carolina, Rhode Island, Iowa, Minnesota, South Carolina, Texas, and Washington). State-level education officials—such as state boards, state departments, state commissioners, and superintendents—develop educational content standards that, depending on state statutes, are either required or recommended in curriculum development. Funding availability may also determine if and how schools implement sex education.

There are two main approaches towards formal sex education: sexual risk avoidance and comprehensive sex education. These categories are broad, and the content, methods, and targeted populations can vary widely between programs.

Sexual Risk Avoidance Education: The foundation of these programs is to emphasize the benefits of abstaining from non-marital sexual activity as a means of reducing risky behaviors, STIs, and teen pregnancy.

- Abstinence-only: In general, abstinence-only programs teach adolescents how to voluntarily refrain from non-marital sexual activity, and stress that abstinence is the only safe and effective way to prevent unintended pregnancy and STIs. They generally do not discuss contraceptive methods or condoms other than to emphasize their failure rates.

- Abstinence-plus: Some programs stress abstinence as the best way to prevent pregnancy and STIs and include information on contraception. Other abstinence-plus programs emphasize safer-sex practices and often include information about healthy relationships and lifestyles.

Comprehensive sex education: These programs include medically accurate, evidence-based information about both sex and abstinence, contraception, and the use of condoms to prevent STI transmission. Comprehensive programs also usually include information about healthy relationships, sexual consent, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

Proponents of sexual risk avoidance education (SRAE) argue that teaching abstinence to youth will delay teens’ first sexual encounter and will reduce the number of partners they have, leading to a reduction in rates of teen pregnancy and STIs. However, there is a limited body of evidence to support that SRAE programs have these effects on the sexual behavior of youth, and some studies have documented no impacts on pregnancy and birth rates.

There is, however, considerable evidence that comprehensive sex education programs can be effective in delaying sexual initiation among teens and increase the use of contraceptives, including condoms, among sexually active youth. Studies repeatedly show that comprehensive sex education is associated with lower pregnancy rates, more consistent condom use, and lower rates of unprotected sex. Despite this growing evidence, 34 states require schools to stress abstinence, or emphasize that abstinence is preferable to sexual activity, if sex education is taught.

Research also shows that comprehensive sex education programs improve students’ health outcomes and understanding, knowledge, and attitudes of a wide range of health topics, including gender and sexual diversity, violence, and healthy relationships.

Gender and Sexual Diversity

For years, research has found that comprehensive sex education with LGBTQ-inclusive curricula is associated with reduced victimization among sexual minority youth as well as reduced adverse mental health outcomes among all youth. Despite the demonstrated effectiveness in improved outcomes, instruction on sexual orientation and/or gender identity (SOGI) is required in only nine states and D.C. and optional in 13 states—if sex education is taught (Figure 3). Among these states, eight require instruction to portray non-heterosexual and non-cisgender identities as unacceptable. In other states, there is either no explicit policy or instruction on SOGI is banned altogether.

Historically, heterosexual and cisgender identities have been the central focus of sex education, but in recent years, advocates have increasingly called for more representation of sexual and gender diversity in curricula. In 2021, approximately 3 in 10 (29.6%) LGBTQ+ students who received any kind of sex education reported that LGBTQ+ representation was positive, while over half (57%) reported receiving sex education without “LGB or transgender/non-binary” topics.

Although sex education content is typically determined by states and school districts, recent actions by the Trump administration may further impede access to SOGI instructional material. In January 2025, the administration issued an executive order officially recognizing only 2 sexes: male and female, which does not account for the complexity of sex and human beings and excludes recognition of gender expansive identities including transgender and non-binary people. In July 2025, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a policy notice restricting the use of federal funding from the Teen Pregnancy Prevention (TPP) program, meaning grantees of this program would no longer receive funding if their educational materials reflected “radical gender ideology” and encouraged “discriminatory equity ideology.” These actions have raised concerns about how gender and sexual diversity may be included in sex education, if at all.

Concern over educational content, particularly sex education, has long been a point of contention for parents. Parents may choose to opt their children out of sex education classes due to personal or religious beliefs. In recent years, parental involvement has evolved into a national debate over how much influence parents should be allowed to have when it comes to their student’s education and personal health decisions, with some calling for a “Parental Bill of Rights.” This movement has gained traction in several politically conservative states and is increasingly reshaping educational curricula in school districts across the nation.

Healthy Relationships and Violence

It is not uncommon for adolescents to experience dating violence (DV). An estimated 1 in 12 teens in 2021 report experiencing physical DV, which can include being hit, injured with an object or weapon, or slammed into something. An estimated 1 in 10 teens report experiencing sexual DV, which includes unwanted physical advances such as kissing, touching, or forced intercourse. Some adolescents, such as female teens and those who identify as LGBTQ, report higher rates of physical and sexual dating violence.

Studies have long shown that comprehensive sex education is associated with lower rates of DV among adolescents and increased knowledge, attitudes, and skills to form healthy relationships. School-based programs that teach DV and intimate partner violence (IPV) prevention have been proven to reduce both DV and IPV among students, with some programs yielding long-term outcomes. Research also shows that comprehensive school-based programs improve students’ knowledge and attitudes towards forming healthy relationships and improve communication skills and intention/consent.

Schools are required to have curricula on healthy relationships in 34 states and D.C., but fewer states (17 and D.C.) are mandated to teach students on sexual consent (Figure 4).

Abortion Knowledge

Abortion is a safe and common medical service that an estimated one in four women will obtain at some point in their life. In 2022, 9% of abortion patients were younger than 20-years-old.

Since the Dobbs decision, 12 states have banned abortion, and another 6 states have implemented early gestational limits between 6 and 12 weeks. The confluence of mis- and dis- information, litigation on abortion access, and policy changes at the state and federal level has made accessing reliable and accurate information on abortion difficult for many. Small shares of 15- to 17-year-olds say they received information about abortion in the past year, primarily through sources like social media, websites, and friends. Fewer than four in ten say they are confident in their ability to get information about abortion services or methods.

Abortion is largely absent from school curricula, including in sex education class. Only California, Colorado, and D.C. require sex education programs to teach about abortion. Six other states—Arkansas, Connecticut, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, and South Carolina—restrict what can be taught regarding abortion. One third of states discourage abortion curricula in sex education programs, and five of these states—Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, North Dakota, and Tennessee—require schools to show students a medically inaccurate depiction of fetal development beginning at fertilization, known as the Meet Baby Olivia video. These “Baby Olivia” laws have been introduced in several other states, including Ohio, West Virginia, and Missouri.

Federal Funding Streams for Sex Education

Although decisions regarding if and how sex education is taught are ultimately left to individual states and school districts, Congress and the executive branch also play a role by providing financial support to programs that focus on preventing adolescent pregnancy. Federal dollars go toward programs that focus on sexual risk avoidance education/abstinence education, comprehensive sex education, or a combination of the two approaches.

Four major programs provide the majority of federal dollars towards education on teen pregnancy prevention: the Teen Pregnancy Prevention (TPP) program, the Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP), the Title V Sexual Risk Avoidance Education Program (SRAE), and the General Departmental (GD) Sexual Risk Avoidance Education (SRAE) program. These programs primarily fund school programs but can also fund churches, juvenile justice programs, and other entities. Other federal programs, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Division of Adolescent School Health (DASH), also provide varying amounts of funding toward sex education initiatives each year.

The four major programs differ in several ways, including by scope and educational approach (Table 1). Notably, the TPP program and PREP use evidence-based, comprehensive sex education models proven to be effective at preventing teen pregnancy, whereas the two SRAE programs stress refraining from nonmarital sexual activity and have historically focused on abstinence-only approaches. While grant announcements and notices from the two SRAE programs required grantees to adopt “evidence-based” interventions and “medically accurate” curricula during the Biden administration, Project 2025’s agenda—which the Trump administration has been closely mirroring in their recent policy proposals—specifically notes that “any [sex education program] lists with ‘approved curriculum’ or so-called evidence-based lists should be abolished.”

The TPP program, established in 2010, is a national grant program that funds organizations to educate adolescents in making healthy decisions to improve their sexual and reproductive health outcomes. The large majority of TPP program participants were served in school settings, and some participants were served in community-based settings, or other places such as juvenile justice centers and clinics. Compared to the pre-pandemic era, larger shares of participants in recent years were served in technology-based and virtual settings.

Also established in 2010, PREP awards grants to state agencies to educate adolescents on both abstinence and contraception, focusing on those who experience homelessness, are in foster care, live in areas with high teen birth rates, or are from minority groups. Like the TPP program, most of the implemented programming took place in school settings during school hours, with a smaller share taking place after school.

Formerly known as the Title V Abstinence Education Grant program established in 1996, the Title V SRAE awards funds to grantees focused on sexual risk avoidance or abstinence until marriage. The GD SRAE program similarly funds programs that exclusively teach abstinence, with a focus on teens experiencing homelessness, teen pregnancy, and domestic violence. An evaluation of the two SRAE programs show that most SRAE programming took place in middle and high schools (74%), while others took place in settings such as community-based organizations, faith-based institutions, and detention centers.

The four programs are appropriated different amounts of federal funding per fiscal year (FY). The TPP program is a discretionary grant program and received $101 million in FY2024. PREP and the Title V SRAE programs, both mandatory spending programs, received $75 million each. The GD SRAE program, a discretionary grant program, received $35 million in funding in FY2024. Of the $286 million of federal dollars dedicated to teen pregnancy prevention programs from these four programs, 38% goes towards programs that focus exclusively on sexual risk avoidance/abstinence education, which has been demonstrated to be less effective at preventing pregnancy in adolescents compared to comprehensive sex education (Figure 5).

Funding for the SRAE programs had only small fluctuations between FY2019 and FY2024 ($100-$110 million), but this has more than doubled since FY2014 when the programs were funded at $51.4 million in total (Figure 6). Federal funding towards comprehensive sex education, on the other hand, has remained steady in the last 10 years, ranging between $170.6 and $176 million.

While federal funding for sex education and other reproductive health services for adolescents has been appropriated by Congress for decades, there have been recent efforts from the Trump administration to cancel or withhold these federal dollars from grantees. The Trump administration recently announced the cancellation of a $12.3 million PREP grant to California after state officials refused to revise curricula in compliance with the president’s 2025 executive order on gender. This executive order refuted the concept of “gender ideology,” and—without scientific evidence—argued that only two sexes exist. Shortly after, the administration sent letters to 46 additional states and territories demanding that all references to “gender ideology” (generally taken to mean reference to transgender people) be removed from PREP sex educational materials. States that fail to comply may also risk losing federal funding like California’s program. As of September 2025, 16 states and D.C. have sued HHS, alleging that these current grant conditions are unlawful, unconstitutional, and harmful to gender diverse youth.

Similar policy changes were also made to the TPP program earlier this summer, but the Trump administration’s actions were blocked by a judge in October 2025. Previous iterations of the House Republican’s 2026 funding bill would have likewise eliminated funding for the TPP program altogether and increased funding for abstinence-only education by $5 million. These actions mirror previous efforts to dismantle comprehensive sex education in the classroom from the first Trump administration, which unsuccessfully tried to cut over $200 million in federal funding for TPP program grantees. The first Trump administration also shifted the TPP focus and funding away from comprehensive sex education and towards abstinence-only education.

The recent policy proposals from the second Trump administration closely align with Project 2025’s agenda, which claims comprehensive sex education promotes sex, prostitution, and abortion. Project 2025’s agenda prioritizes curricula that emphasizes sexual risk avoidance, arguing that any other program should not be eligible for federal funding. President Trump’s proposed 2026 discretionary budget, which is both a funding request to Congress and documentation of administrative priorities, would eliminate support for the TPP program as well as the GD SRAE program, claiming that both are “duplicative” of PREP and Title V SRAE, respectively.