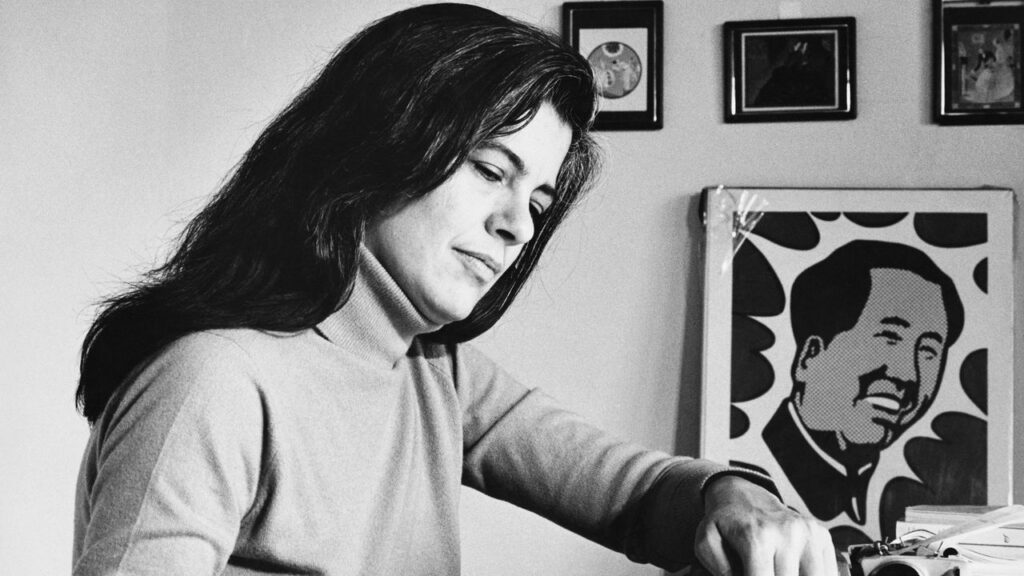

“Susan Sontag Tells How It Feels to Make a Movie,” by Susan Sontag, was originally published in the July 1974 issue of Vogue.

For more of the best from Vogue’s archive, sign up for our Nostalgia newsletter here.

Filmmaking is a privilege and a privileged life. Filmmaking is nitpicking, anxiety, fights, claustrophobia, exhaustion, euphoria. Filmmaking is feeling almost undone by sentimental goodwill toward the people you’re working with part of the time, feeling misunderstood or let down or betrayed by them the rest of the time. Filmmaking is catching inspiration on the wing. Filmmaking is flubbing the catch, and sometimes knowing the fool that’s to blame is yourself. Filmmaking is blind instinct, petty calculations, smooth generalship, daydreaming, pig-headedness, grace, bluff, risk.

That the sense of risk which accompanies making a film is so much steeper than the one that goes with writing seems, as professional secrets go, disconcertingly well-known. When I tell friends I’ve finished a story or an essay or a novel, no one inquires solicitously: “Are you pleased with it?” And: “Did it come out the way you hoped?” But this is just what I am usually asked when I’ve finished a film. The implication is that to write means taking a direct route between one’s plans and their execution. A writer’s intentions and hopes have no place to go except to end up, clearly reflected, in the finished writing. At any rate, if they don’t, it is not the writer himself or herself who is likely to be aware of the lag. But with a movie, everyone (including people who have never watched one being made) supposes that the path between the filmmaker’s intention and the completed film is strewn with implacable hazards and dingy pressures, that any film is the more or less damaged survivor of an appalling obstacle race.

People aren’t mistaken. Writing means knowing what’s in your head that’s interesting, having the craft to get it out, having the patience to sit long enough at a table to get it down. (And having the judgment to know when it could be better. And the tenacity to keep revising until it’s as good as you can make it.) Writing is between you and your demons; between you and that quaint nineteenth-century machine, the typewriter. It’s an inside job, essentially: an act of the will. But willpower will never take you all the way in making a film. Directing a film means trying to be smart not just about oneself and the world and our glorious English language, but being dependent on and trying to be smart about uncontrollable capricious elements, like actors and machinery (twentieth-century stuff) and weather and money—more likely than not to get out of hand. Where everything can, it often goes wrong. Orson Welles was scarcely exaggerating the matter when he said, “A director is someone who presides over accidents.” Yet for someone like myself, addicted to the ascetic solitude of writing, it is a welcome release to get out there and do battle with the accidents, trying to “preside” over them. However dismaying is the gap between your idea prior to the shooting, and what you finally have in the can, you have to feel gratitude for what providence has brought as well as bad luck has spoiled. It’s relief to hear other voices than my own. It’s good to be a bit battered and bruised by that reality over which one suspects, sometimes, one has gained easy (“willful”) victories alone at the typewriter.