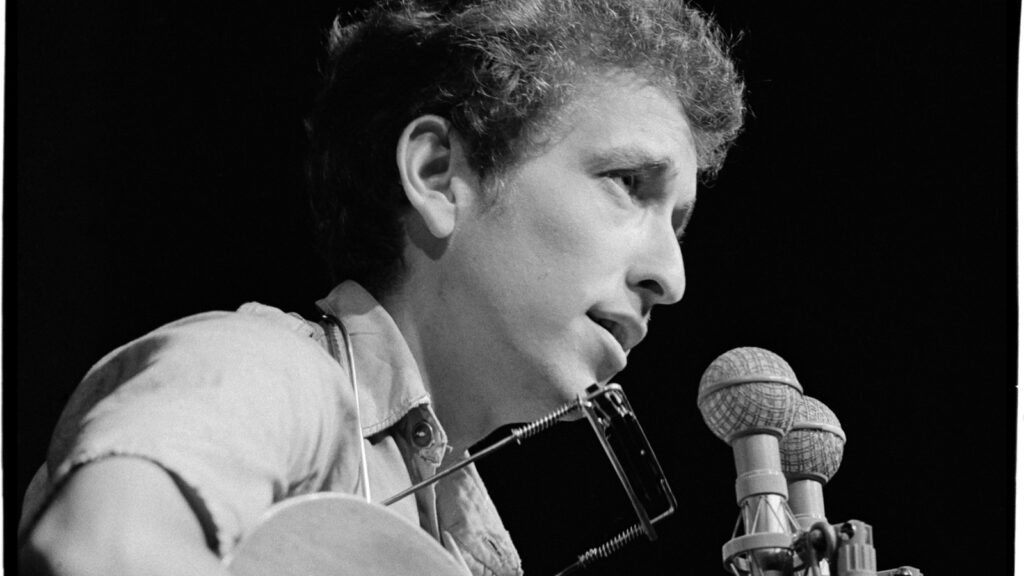

In late 1961, barely a year after he’d arrived in New York City from the Midwest, Bob Dylan already contained multitudes. The proof arrives early in Through the Open Window, the 18th edition of Dylan’s ongoing Bootleg Series. That fall, Dylan, then only 20 years old, recorded his first album with producer John Hammond. Among the many unheard tapes crammed into the box’s eight discs are leftovers from those sessions, including an alternate version of the traditional “Man of Constant Sorrow.” Sounding like an unsure Boy Scout asking for the approval of his Scoutmaster after attempting a square knot, Dylan lays down a take and then asks Hammond, “Did you get that? … Did you like that?” But when Hammond asks if anyone else had cut the song already, a different Dylan emerges. “Not that way … A different way, I guess,” he says, before mentioning a peer on the scene who’d already released a version of the song. “Judy Collins did it. But not a version … not like that. That’s a different one.”

On a compilation that gives us any number of glimpses into Dylan’s growth and creative process before he went electric, that moment is both a throwaway and a deep reveal. Dylan’s version of “Man of Constant Sorrow” isn’t vastly superior to anyone else’s; he doesn’t rock it out like he did with other folk and blues songs he was playing at the time. But his subtle brush-off of Collins is a sign of the cocky and brash kid already beginning to emerge — the same one who could cut down people down to size on his way to redefining himself and jolting both the New York folk scene and the world of pop at large.

Taking in the years 1956 to 1963, Through the Open Window serves as an unofficial companion to last year’s A Complete Unknown biopic. It starts before that entirely credible and affecting film did, with a teenage Robert Zimmerman romping through the Shirley & Lee hit “Let the Good Times Roll” in a St. Paul music store (the first known recording of Dylan). The box wraps up about two years before Dylan’s rampaging performance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, depicted in the movie. As with the film, it tells a familiar story: earnest and ambitious but seemingly fumbling kid with a mysterious background moves to the big city, ingratiates himself with a music community, knocks everyone’s beret’s off with his skills and songs, and then begins leaving behind all those inspired by news headlines in favor of more ambitious, poetic, and personal ones.

Needless to say, that story has been told on his official releases of the era, from Bob Dylan to Another Side of Bob Dylan and Bringing It All Back Home and beyond. But Through the Open Window brings us another side of that transformation. Using a plethora of sources — unearthed club recordings, tapes of Dylan singing in people’s homes or at rallies, outtakes from recording sessions, stage remarks — it allows us to eavesdrop as Dylan moves from the Midwest to New York, hits the Village coffeehouse and club circuit, tries out songs for friends, interacts with fellow performers, plunders some of their repertoire (especially that of his mentor Dave Van Ronk), even interacts with a gushing radio DJ. As familiar as that map is, we’ve never been afforded such a granular document of that metamorphosis, and how fast, relentless, and often breathtaking it could be.

Compiled by Steve Berkowitz and Sean Wilentz, the massive box (also available in a two-disc distillation for Dylanologists on a budget) includes a certain amount of material already available on previous Bootleg Series editions and other Dylan compilations. But 48 of its cuts have never been heard by anyone other than collectors and Dylan’s gatekeepers, which lends added weight to its historic value. We finally get to hear one of his fall 1961 sets at Gerde’s Folk City: not the one that New York Times critic Robert Shelton saw, resulting in the rave review that landed Dylan his record deal, but one a few nights later, which is close enough. We get the first-ever live performance of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which shows how fully formed the song was from the start. Not all of these rarities live up to their legends: that Folk City set is a bit anticlimactic, and “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues,” his infamous dig at the nutjob conservative group, is a little too cute. But their appearance on any Dylan collection is long overdue.

Along the way, though, Dylan’s transformation from frisky, plucky folk upstart — a walking, talking, cap-wearing version of the Anthology of Folk Music collection everyone was discovering at the time — to master of his domain is heard in large and small ways. Recordings of him playing Woody Guthrie and Jesse Fuller songs before he moved to New York show how fully invested he already was in American vernacular music; his sound and persona were already in the works before he stepped into his friend’s car for that ride to New York City. We also hear deeper examples of the way he pillaged the sources around him. On a recording of an early, bumpier version of “Tomorrow Is a Long Time,” he mentions the “tape recorder machine” in front of him as if he were auditioning for a Guthrie biopic.

As anyone who saw his early New York performances still attests, Dylan was also legitimately funny, and the comic timing on display in these tapes is another revelation. At various shows, he charms audiences with tales of almost getting hit by a bus on the way to the venues, the idea of written setlists (“I don’t much believe in lists … I went around and I copied down all the best songs I could find off everybody else’s lists,” he cracks), or a hokey fake-hootenanny movie he’d just seen in Times Square (“Don’t tell anybody,” he jokes, adding, “42nd Street, a very hip street”). It’s a chatty, endearing side of Dylan we’ve rarely, if ever, heard onstage since. There are also hints of his post-folk future in an early original, “I Got a New Girl,” which he croons as if prepping for Self-Portrait years later, and the piano-locomotive “Bob Dylan’s New Orleans Rag,” a Times They Are A-Changin’ outtake that pounds with a rock & roll heart. No purist was he, right from the start.

As the box hurtles toward its finale — the complete recording of his fall 1963 Carnegie Hall concert, which cemented his stature — Dylan’s feel for traditional songs grows deeper, and the growth in his own songwriting, so quickly, remains astounding. The transformation of “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” into the somber beauty it became is remarkable, and a version of “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” taped at a friend’s place in Los Angles, is mesmerizing. By the time he arrives at Carnegie Hall, with three albums under his belt, Dylan is fully in command of his voice, songs, and presence. He sings his “North Country Blues” as if he were a member of that devastated coal-mining family before moving onto “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” which feels like a statement of its own: That was the feel of folk music then, but this is folk music now, and on his terms.

That tape, which takes up the last two discs of Through the Open Window, is also unexpectedly illuminating. The audience is hushed during his protest songs and laughs adoringly when he talks about an academic not quite understanding the title phrase of “Blowin’ in the Wind.” (“Now this guy’s gonna be a teacher!” Dylan retorts.) They sound in awe of him, as they should: The recording stands as one of Dylan’s greatest (unreleased) concert albums. In that moment, on that night, the very thought that he would largely abandon that approach and some of those songs — he would never again play a few of them, like “Lay Down Your Weary Tune” — must have been unfathomable, and we share their discombobulation. Yet move on he did, plugging in just over a year and a half later and leaving that period in the Carnegie Hall dust. But as Through the Open Window makes clear, he was always on the verge of slamming one window shut and opening another to an entirely different world.